I've been thinking about dynamic pipelines lately, where the DAG structure emerges at runtime instead of being defined upfront. My first instinct was honestly skeptical.

If you don't know what your pipeline will look like before you run it, maybe you're designing it wrong? In traditional ML engineering, you should know your pipeline structure. Training, evaluation, feature processing... these are knowable. Defining them upfront gives you reproducibility, debuggability, and the ability to reason about costs before you commit compute.

So why ship dynamic pipelines in ZenML? Because specific use cases emerged that warranted a second look.

The AutoML Parallel

This skepticism recalls the AutoML era. The promise was: "just search the hyperparameter space exhaustively, who needs domain expertise?" Hypergrid search across everything! We don't need data scientists anymore!

That didn't pan out. Expertise still matters. Brute-force search often finds spurious optima or just burns compute. The engineers who understood their domains (who knew which hyperparameters actually mattered) still outperformed the exhaustive searchers. They were also able to work more efficiently.

Dynamic pipelines have a similar smell if you're not careful. The temptation to fan out to 1000 instances because "surely more exploration == better results" is real. But an engineer who knows their domain knows, for example, that for a given use case there might be just six or seven data sources that actually matter. The rest is noise. Either you're wasting money and tokens, or you're polluting the context window with irrelevant information.

When Dynamic Pipelines Actually Make Sense

What changes the calculus? Agents. Specifically, the "deep agent" pattern.

Here's what makes something genuinely need dynamic structure:

- A supervisor spawns sub-agents to arbitrary depth

- It can roll back from dead ends

- It fans back in with just the useful results

- You genuinely don't know the DAG upfront (and that's not bad design, it's the nature of the problem)

There's also the "context rot" problem. What happens when an agent's context window fills up and performance degrades? Sub-agents isolate context so the parent only gets the final answer, not the 20 tool calls that produced it.

This is different from traditional ML workflows where you know the structure beforehand.

But here's the catch: more exploration isn't always better. And you still need hard constraints. Dynamic pipelines can be powerful for agents and genuinely variable workloads. They're not a substitute for knowing your domain.

The Separation of Concerns

Here's the key design insight: separate what the framework should control from what the agent should control.

Why does this matter? The agent decides what to explore; ZenML handles the orchestration. You get the robustness of a pipeline framework (retries, caching, lineage, the ability to debug a specific step) without losing the flexibility agents need to explore.

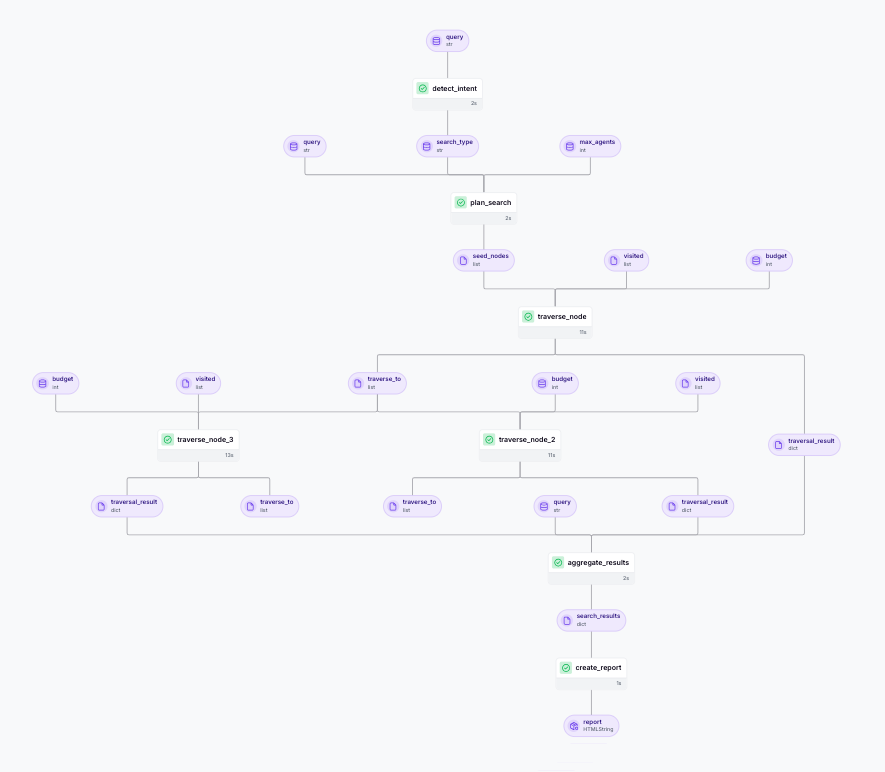

A Concrete Example: Hierarchical Document Search

To illustrate these patterns, we built a toy example: a hierarchical document search agent. Simple queries stay simple (fast keyword search). Deep queries fan out to traversal agents that explore a document graph, with configurable depth and max-agent limits.

The DAG ends up looking like this:

Each traverse_node is a separate step, created at runtime, with its own artifacts, retries, and lineage. The agent decides "answer found" or "traverse deeper," and ZenML handles spawning the next round of steps.

This is a toy example to demonstrate the patterns. For more complex real-world examples of companies running dynamic workflows in production, see the next section.

Industry Examples: What Others Have Learned

We're not the only ones grappling with when dynamic or agentic workflows make sense. Here's what other companies have discovered.

Hex: "Our first attempt didn't go super well"

Hex builds AI-powered data notebooks where users ask questions and the system dispatches multiple agents to handle different stages: planning what to do, generating SQL, transforming data, creating charts. Each agent operates somewhat independently, and the results fan back together into a coherent analysis. This is exactly the kind of dynamic, multi-agent orchestration where you don't know the DAG upfront.

Their candid admission:

"Our very first attempt at agents in prod... it didn't go super well. We were getting too high of entropy."

Their fix? Constrain the plan space. Instead of letting the agent invent arbitrary step types:

"We were more prescriptive about the types of plans that could be generated."

They also treat context as a budget problem:

"We are very aggressive about the way that we keep things out of context... it's very much this Michelangelo carving a sculpture thing of trying to get rid of all the stone that shouldn't be there."

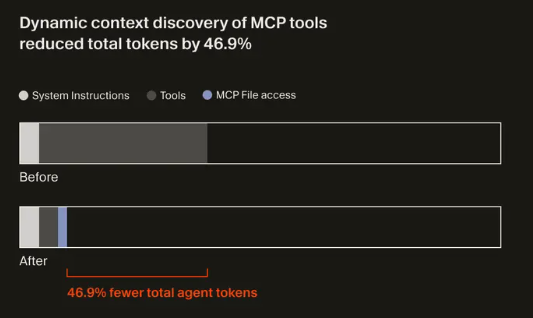

Cursor: 46.9% Token Reduction Through Dynamic Context

Cursor builds AI coding agents that need to understand large codebases. The challenge: how much context do you inject upfront versus letting the agent discover what it needs? This is a dynamic pipeline problem because the agent's trajectory through the codebase depends on what it finds at each step. You can't pre-define which files will be relevant.

They chose dynamic discovery:

"As models have become better as agents, we've found success by providing fewer details up front, making it easier for the agent to pull relevant context on its own."

The result: a 46.9% reduction in total agent tokens (statistically significant).

Their key insight on budgets:

"We believe it's the responsibility of the coding agents to reduce context usage."

The Cross-Company Pattern

What Hex and Cursor have in common:

- Budgets are design inputs. Both companies treat token limits and context windows as hard constraints to design around, not afterthoughts. Hex carves context like a sculptor; Cursor reduced tokens by 46.9% through dynamic discovery.

- Constrain the action space, not the ambition. Hex learned this the hard way: let agents be creative within tightly defined step types. Don't let them invent arbitrary plans.

- Dynamic discovery beats static injection. Instead of cramming everything into the prompt upfront, let agents pull what they need. This improves both efficiency and response quality.

Key Technical Patterns

If you're building dynamic pipelines in ZenML, here are three patterns that come up repeatedly. These relate to how ZenML handles artifacts (the data passed between steps) when the DAG structure isn't known until runtime. (For more information, please read our documentation page for dynamic pipelines.)

Pattern 1: .chunk() vs .load()

In a dynamic pipeline, you often need to loop over a collection of items and spawn steps for each one. ZenML provides two ways to interact with artifact data, and understanding when to use each is crucial.

When you're looping through artifacts:

.chunk(idx)creates the DAG edge. It tells the orchestrator "this step depends on item X from upstream.".load()gets the value for your Python control flow decisions.

You need both: chunks for wiring, loads for decisions.

Pattern 2: Budget limiting at two layers

Dynamic pipelines can explode in size if you're not careful. A user asking for max_depth=100 could spawn thousands of steps. Protect yourself at two layers.

First, clamp user inputs at pipeline entry (protects orchestration):

Then decrement budget per-step (protects traversal). The step updates the remaining budget; the pipeline uses it to decide whether to spawn more steps.

Pattern 3: Bounded expansion

Even with budget limits, you can still get combinatorial explosion if each step spawns many children. Cap the fan-out per node:

Cycle avoidance with visited tracking prevents infinite loops.

Gotchas to Watch

Artifact loading is synchronous. When you call .load(), it synchronously loads the data. For large artifacts, pass outputs directly to downstream steps instead.

Logging isn't thread-safe yet. Logs from parallel steps may be mixed up when running concurrently. Known limitation we're working on.

When NOT to Use Dynamic Pipelines

Use static pipelines when:

- You know the pipeline structure beforehand (most standard ML workflows)

- Training, evaluation, feature processing... if these are knowable, define them upfront

- You need simpler debugging and cost prediction

In general, default to static pipelines for most use cases. Don't assume you're clever enough to need dynamic.

Avoid dynamic pipelines for:

- Real-time agents or chat interfaces (ZenML is for batch, not streaming)

- Simple single-agent workflows (overkill)

- When "I'll just fan out to everything" is a substitute for understanding your domain

That last one is key. If you can't articulate why you need dynamic structure, you probably don't.

The Right Question

The question isn't "are dynamic pipelines good or bad?"

It's: when do you actually need them, and when are you just avoiding the work of understanding your domain?

The best setup combines:

- Dynamic fan-out with hard constraints

- Budget limits and depth caps

- Expert-informed starting points

The other place dynamic pipelines earn their keep: failure handling. If you're fanning out to N workers and some might fail (an API times out, a Docker image doesn't exist, a downstream service is flaky), you want per-step handling. Retries. Fallbacks. The ability to resume from the last good state. That's where having this at the pipeline level, not just inside a single step, actually matters.

Where This Leaves Us

I started skeptical, and honestly, I still am for most use cases. If you're running standard ML workflows (training, evaluation, feature engineering), static pipelines remain the right choice. They're simpler to debug, easier to reason about, and you can predict costs before you run.

But for the specific cases where you genuinely don't know the DAG upfront? Where agents need to explore, where the workflow shape depends on what you find at runtime, where you need per-step failure handling across a dynamic set of workers? That's where dynamic pipelines earn their place.

The key is knowing the difference. Don't reach for dynamic pipelines because they sound powerful. Reach for them when you've thought through your domain and concluded that static structure genuinely can't express what you need.

And when you do reach for them, constrain them. Budgets. Depth limits. Bounded fan-out. The companies who've made this work in production all learned the same lesson: dynamic structure with hard constraints beats both rigid pipelines and unconstrained exploration.

Dynamic pipelines are currently supported for the local, local_docker, kubernetes, sagemaker, vertex, and azureml orchestrators. Check out the hierarchical document search example to see these patterns in action, or dive into the documentation for the full API reference.

.png)